Update. 1/12/20. Amplixin is said to be a revolutionary line of hair growth products for men and women. At the heart of the Amplixin is what they call the Ampligro Complex, a combination of red clover and other substances. This Amplixin Review will cover the different products and the research and I'll also try to decipher which might be the key ingredients too. Does Amplixin work or is it a scam? Let's see what we can discover about it.

Other Hair Growth Reviews

For more insights, see these additional reviews:

- Viviscal Review

- Amla fruit review

- Nutrafol vs. Viviscal

- Halo Beauty Review

- Castro Oil and Hair Growth Review

- PHYTO Re30 Review

- My Biotin Pro Clinical Review

See those reviews for much more insight.

What is the Amplixin?

Amplixin hair system consists of the following products

- Stimulating shampoo

- Revitalizing conditioner

- Scalp therapy shampoo

- Hydrating masque

- Intensive growth serum

- Advanced biotin + supplement

All these names sound pretty impressive. Let's take a quick look at each product next.

Amplixin Hair Growth System Products

1 Stimulating Shampoo

They call this the first step in their hair support system. The shampoo contains

- Acetyl-Tetrapeptide-3

- caffeine

- red clover

- saw palmetto

Red clover might also reduce inflammation inside hair follicles. Both red clover and saw palmetto are known to block DHT, an enzyme (called 5 alpha reductase) involved with the production of DHT.

The hormone DHT (dihydrotesosterone) plays a role in hair loss. The substance acetyl-Tetrapeptide-3 appears to improve collagen and other hair follicle-supporting proteins. These are called ECM proteins (extracellular matrix proteins).

Some research also finds topical caffeine plays a role in stimulating hair growth. In one investigation, isolated follicle cells bathed in caffeine and testosterone for several hours showed more hair growth than follies only bathed in testosterone. The conclusion was caffeine suppressed testosterone effects on hair loss.

See the caffeine shampoo review for more insights.

2 Revitalizing Conditioner

The conditioner also has and red clover (Trifolium pratense), which we also saw in the shampoo too. In theory, it might work in synergy with the shampoo.

3 Scalp Therapy Shampoo

This other shampoo is said to contain ingredients to encourage a healthy scalp. That's vague. I can't tell from the ingredients if the Scalp Therapy Shampoo adds anything significant to the Amplixin system.

4 Hydrating Masque

The hydrating masque is to be used in conjunction with the scalp therapy shampoo. It is said to improve moisture to dry and itchy scalps. After using the scalp therapy shampoo, apply the hydrating masque to the hair and leave on for 3-5 minutes. If your scalp isn't dry or itchy, you might not need the hydrating masque.

5 Intensive Hair Growth Serum

The growth serum is a product you leave on the hair and do not rinse off. The serum contains ingredients that stimulate roots and promote healthy hair growth. What are those ingredients? Well, it has biotin, which can help hair and nails grow. Biotin does not grow new hair; rather, it helps what you have left grow faster.

While the intensive hair growth serum does contain caffeine, it does not have red clover, saw palmetto or acetyl Tetrapeptide-3 like the stimulating shampoo does.

6 Advanced Biotin + Supplement

As the name implies, the Advanced Biotin + supplement contains biotin plus other vitamins and minerals. Two capsules of this supplement gives you 8000 mcg (8 mg) of biotin, which is more than the average biotin supplement has. As mentioned, biotin can help hair and nails grow faster. But, this vitamin would not be expected to promote new hair growth.

This supplement also provides 40 mg of horsetail. Some research finds horsetail might help hair growth in women. Much of this research involves a multi-ingredient hair growth supplement called Viviscal.

See the Viviscal review for more insights.

What Is The Ampligro Complex

The Ampligro Complex is how the company refers to ingredients that block the DHT hormone. Elevated DHT levels are linked to hair loss. The Ampligro Complex is mostly made up of saw palmetto, red clover, caffeine, and acetyl-Tetrapeptide-3.

Amplexin Ingredients

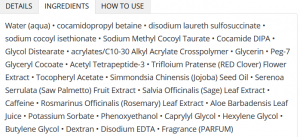

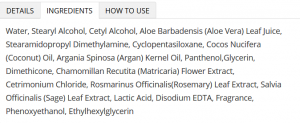

There are 6 different Amplexin hair products. Here are screenshots from Amplxin.com of the ingredients in the 6 different products side by side:

Shampoo | Conditioner |

Scalp Therapy | Hydrating Masque |

Intensive Growth Serum | Amplexin Vitamins |

Amplexin Active Ingredients

The product website lists 6 different clinical studies as proof of the results of these hair products. If these 6 different studies are the proofs of the effectiveness of Amplixin, then we can use them to boil the products down to their key ingredients. The 6 clinical studies highlight these ingredients

- Red clover (Trifolium pratense)

- Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens)

- acetyl-Tetrapeptide-3

- Caffeine

These 4 ingredients are mentioned several times in the clinical studies mentioned on the product website. As such, I think they are important to your results with Amplixin. I believe these ingredients primarily make up the Ampligro Complex.

While Saw palmetto and red clover are common dietary supplements found in hair and skin products, with Amplixin, they are applied topically to the hair and scalp, rather than taken orally. These two ingredients are thought to help hair growth by blocking DHT, a hormone linked to hair loss.

Additionally, saw palmetto is also a key ingredient in prostate supplements.

How Does Amplixin Work?

From the ingredients in the various products (shampoos, vitamins, serum, etc.) it appears they are supposed to help hair growth in the following ways:

- Block DHT from forming (by blocking the 5 alpha-reductase enzyme)

- Reduce inflammation in follicles

- Improve collagen and other protein production in /around hair follicles

- Moisturize hair and help it stand up better

Sounds good, but is there any proof for this? Let's look at the Amplixin research next.

Amplixin Research

While there are various hair growth studies on some of the ingredients, such as those mentioned above, Amplixin products themselves, seem to not have been tested clinically to see if they work. The product website does provide some impressive before and after pictures, however.

Who Makes Amplixin

The company website is Amplexin.com. The company is called Lia Wellness Inc. The company is located in Florida.The company address listed on the product website 16850 Collins Ave. Suite 112-350 North Miami Beach, FL 33160. This address (minus suite 112-350) corresponds to a strip mall containing many businesses such as GNC, Subway, and even a UPS Store, among others.

The person in charge of the company is named Val Narodetsky. This name is also associated with another company called Ez Shapers (EzShapers.com) which sells shapewear for women.

Contact Amplixin

The company phone number is: 888-791-9o96. Another phone number located is 786-708-2131.

Return Amplixin

I suggest you call the company first to receive specific instructions to return products. The address they list for returns is 211 S. 9th Street, Columbia, PA 17512. This address is the same as another company called BV Global Fulfillment. I think this may be the company that ships Amplixin products.

How Much Does Amplixin Cost

These were prices listed on the company website when this review was updated:

| 1 month supply | 2 month supply | 3 month supply | |

| Stimulating Shampoo | $29.99 | $59.99 | $89.99 |

| Revitalizing Conditioner | $26.99 | $49.99 | $79.99 |

| Scalp Therapy Shampoo | $28.99 | $56.99 | $84.99 |

| Hydrating Masque | $29.99 | $59.99 | $89.99 |

| Intensive Growth Serum | $29.99 | $59.99 | $89.99 |

| Adv. Biotin Supplement + | $26.99 | $49.99 | $79.99 |

These prices do not include shipping.

Amplixin Products are also on Amazon.

Where Can You Buy Amplixin?

Amplixin.com would be the most popular place. It's possible some beauty salons may carry it too. It doesn't look like you can purchase these products from Target, Walmart, Ulta, Sephora, CVS, RiteAid, etc. I like did not see it at Bed Bath and Beyond the last time I was in that store.

How Long Until You See Results?

The product website says at least 4 months of use is needed. The product website does not provide clinical proof for this duration of time but, since hair tends to grow slowly, this makes some sense.

Can Amplixin Regrow Hair That's Fallen Out?

No, and the company does not say it does this either. At best, Amplixin might help you keep the hair you have left. But it will not regrow back hair that has already fallen out. If Amplixin works, the sooner you starts the regimen might mean less hair would fall out.

Amplixin Side Effects

Amplxin products are safe in the vast majorly of people. Besides the general caution of avoiding getting the products in your eyes, tell your doctor if you take the Amplexin vitamins.

The Amplixin multi-vitamin contains a lot of biotin. As my supplement side effects review pointed out, biotin can make it seem like you have hyperthyroidism when you really don't. It may interfere wither other blood tests as well such as those for insulin and testosterone.

Amplixin FAQ

1 Where are they made?

Products are made in America.

2 Does It Contain Sulfates?

All Amplixin products are sulfate-free. They are also paraben-free and cruelty-free.

3 Can Men use Amplixin?

Yes. The product website says both men and women can use these products. Some of the research I saw on the ingredients involved men, which says these products are for both genders.

4 Does Amplixin Contain Minoxidil?

No. None of the Amplixin hair products contain Rogain (Minoxidil), the only FDA-proven substance to grow hair.

Amplixin Before And After Videos

Here are two video reviews of Amplixin I located. To be fair, I included a positive video and a not-so-positive video:

Positive Review

Not So Positive Review

Amplixin Guarantee

All bottles of Amplixin products come with a 60-day money-back guarantee. The 60-day guarantee starts when you order the products -not when you receive them. You have to return the bottles (used or not used) to get a refund.

Since the company recommends 4 months of use before you notice a difference, this guarantee will not refund all the money you spent on Amplexin if you use it long-term.

Can You Use Amplixin With Viviscal?

Viviscal is one of the best-known hair growth supplements. While no studies have shown Amplixin works better with Viviscal, I can see the logic behind wondering if they might work better together – attacking hair loss from external (shampoo) and internal (Viviscal) angles.

While some have reported very good results with Viviscal, it would take research to know if the results of Amplixin + Viviscal would be better than either product by itself.

My Suggestions

If you purchase all the Amplixin products, it can be expensive. So, if you want to test this and see if it works for you, why not start with only one or two products first. I suggest Amplixin Shampoo and conditioner because these have DHT blocker ingredients like saw palmetto, red clover.

If after a few months, you think you see a difference, go ahead and add in one or two other of their products to see if they help more.

For what it's worth I think people can save money on the Amplixin Multi-vitamin and just buy biotin and horsetail instead.

What I Liked And Didn't Like

Here's a quick rundown of what I liked and didn't like about these hair products.

| Liked | Didn't Like |

| Contains ingredients which block DHT | Expensive |

| Some positive reviews | Too many different products |

| Lack of clinical studies |

Your opinions may be different than mine.

Does Amplixin Really Work?

There are many online testimonials about how well Amplixin works. Likewise, there are also those who are less enthused. I didn't try Amplixin so I can't know for sure if it works or not. I also don't know how it stacks up to hair growth supplements like Nutrafol or Viviscal. Because I think these products are expensive, I suggest starting with only 1 or 2 of their products and use them for a few months before committing to the entire hair growth system. Did Amplixin work for you? Let me know.

What about lavender oil regrowing hair?

Here is my video review of lavender oil hair growth research

https://youtu.be/AcuHoAZ2SdA

Hope it helps!

I received a bottle delivered by Prime….no paper work in package….I did not order this

bottle of Amplixin…….Need to have it returned…do not know where to sent it to.

Please advise as to where to send it back.

Bonetti, if Amplixin was delivered by Amazon Prime, contact amazon and they can help you with that. I looked and found this page on Amazon

https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=201821690

At the bottom of the page is a contact link. Click that and Amazon should be able to help you return it.

Also check your credit card. If it was delivered to you, there may be a charge on your credit card too.

Let me know what happens or if you have any other questions

Hey Joe, how do you do it? I just saw an ad for Amplixin today! You must be psychic!

Thanks for this 🙂

Hi Rebecca, My mom always said she was psychic – maybe I inherited it a bit of that power – or maybe I saw the same ad you did 🙂

Either way, I’m glad I could help 🙂